Why I Ditched OpenClaw and Built a More Secure AI Agent on Blink + Mac Mini

A case study in building a personal AI agent with open-source tools and zero exposure to the public internet

The promise and the problem with OpenClaw

OpenClaw recently took the developer world by storm. Within weeks, thousands of people had set up their own personal AI assistant. An always-on digital chief of staff that could manage email, handle calendar invites, automate browser tasks, and chat with you across messaging apps like Telegram and WhatsApp. It ran on hardware you own, like a Mac Mini or a cheap cloud server, which meant your data stays under your control. The appeal was obvious.

Then security researchers started looking under the hood.

They found thousands of OpenClaw setups that were accidentally wide open to the Internet. Anyone who knew where to look could access the owner's shell, browser automation tools, and API keys. The root cause was a design choice: OpenClaw's main service, by default, listens for connections from any network instead of just the local machine. Its security features are still new and under-tested. The gap between "I got it working" and "it's exposed to the world" is dangerously small.

The community responded with workarounds: layering on firewalls, VPN tunnels, and reverse proxies. These were patches on a system that wasn't built with security at its core. OpenClaw was designed as a single-user local tool that organically grew into something much bigger. Security was bolted on after the fact instead of baked in from the start.

I wanted everything OpenClaw offered: a personal AI agent on my own hardware, connected to my real tools, available around the clock. But I also wanted a system where the secure setup is the default, without requiring constant hardening and maintenance.

Why I actually needed this

My digital life is a bit chaotic. My downloads folder has 847 files in it. Some are things I need to keep (tax documents, visa paperwork, that one PDF about fixing my dishwasher), others are garbage I downloaded once and forgot about. I can't tell which is which without opening every single one.

My Gmail inbox has 3,200 unread emails. I miss appointments because calendar invites get buried. I have recipes saved across email, Notes, bookmarks, and screenshots, and when I want to make that pasta dish I had three months ago, I have no idea where I saved it. I bookmark articles to read later and never look at them again.

What I wanted was an AI that could look at my downloads folder every week and tell me "these 15 files are probably safe to delete, these eight look important and need filing." An assistant that could triage my inbox in the morning and surface the five things that actually need my attention. Something that could scan my calendar and remind me "you have a dentist appointment tomorrow at 2pm, and based on traffic you should leave by 1:30." An agent that could remember where I saved that recipe, or find the hiking trail recommendations my friend sent me six months ago.

I also wanted separation. I wanted a general-purpose assistant for everyday tasks (email, calendar, recipes, research) and a separate agent for handling more sensitive things like medical questions or financial planning. These contexts shouldn't mix. My recipe searches shouldn't live in the same conversation history as questions about retirement accounts.

OpenClaw could theoretically do all of this, but the security posture made me uncomfortable. An agent that reads your email and has access to your file system is one of the most sensitive pieces of software you can run. Having it accidentally exposed to the internet because of a misconfigured firewall wasn't acceptable. So I built one that I could actually trust. It took about two weeks, a Mac Mini, and two key pieces of open-source software: Blink (for running the agent) and Tailscale (for keeping it private). The whole stack is free to run with no subscriptions, no vendor lock-in, no cloud dependency.

Here's how it works.

The tech kit I used to make this possible

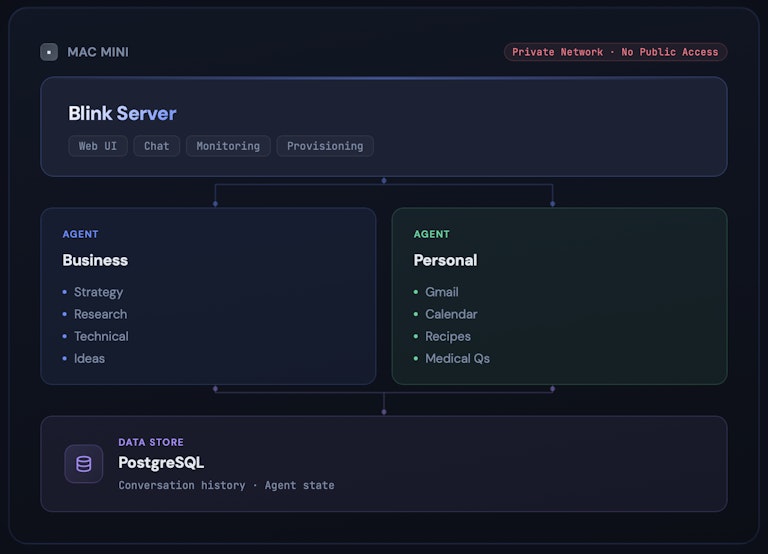

Blink is the agent platform. It's open source, available on GitHub, and free to use. Think of it as the operating system for your AI assistants. It handles running agents, storing conversation history, managing connections to tools like Gmail or Google Calendar, and deploying updates, all inside isolated containers (essentially, separate virtual rooms that can't see into each other). Where OpenClaw runs everything in one big process, Blink gives each agent its own sealed environment. It also doubles as your management interface: the Blink Server ships with a built-in web UI where you can chat with your agents, monitor their status, review conversation history, and manage deployments, all from a single browser tab. No separate dashboard to install, no React app to host, no extra service to configure. You deploy Blink, open the UI, and you're working.

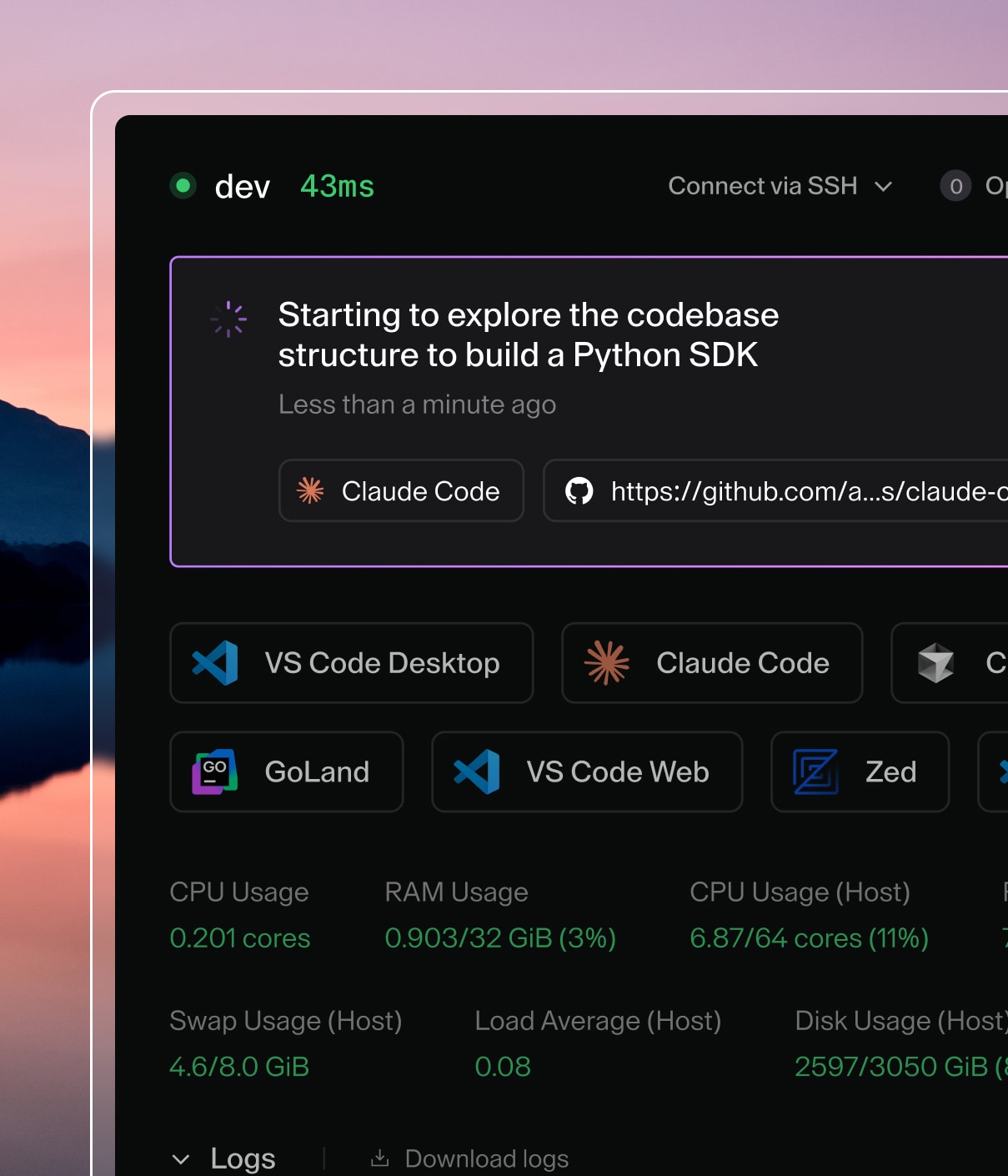

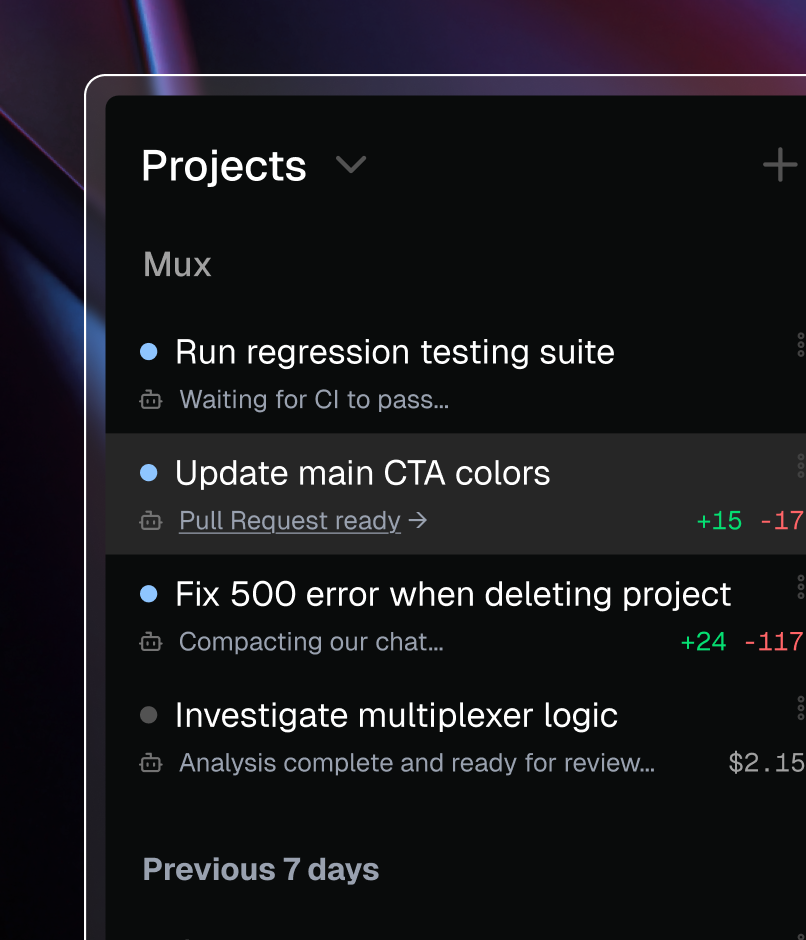

Mux is the development tool. It lets me run multiple coding sessions side by side, each working on a different feature or experiment. This matters because a great AI agent isn't built in one sitting. It takes dozens of iterations to get the behavior right. Mux makes that iteration fast.

Mac Mini M4 is the hardware. Apple's latest compact desktop has more than enough power to run the entire system: the agent platform, the database, and the networking layer, all at once. It idles at about 10 watts, which is less than a desk lamp. It sits on a shelf, plugged into Ethernet, and just runs.

Tailscale is the security layer. It's also open-source at its core (built on WireGuard) and free for personal use. It creates a private, encrypted network between your devices. Once the Mac Mini joins this network, it becomes invisible to the public internet. There are no open ports, no public web addresses, nothing for an attacker to find. The only way to reach the machine is to be on the same private network, authenticated by your identity. Setup takes about ten minutes.

Plumbing this into my routine

Everything runs on the single Mac Mini with four components in one box:

The Blink Server manages agents, handles deployments, and serves the built-in web UI. There's no separate frontend to deploy, no additional service to maintain. You open https://your-mac-mini:3005 over Tailscale and you're looking at a clean interface where you can chat with any of your agents, inspect their logs, provision new ones, and push updates. For a single-box deployment, this collapses the entire stack (runtime, routing, and UI) into one process. Critically, it only accepts connections from the local machine and the Tailscale network, never from the outside world.

Agent Containers are the individual assistants, each running in its own isolated container with its own storage, conversation history, and credentials. I run two. My business agent handles strategy questions, research tasks, and technical ideation. It's where I think out loud about architecture decisions or ask for competitive analysis. My personal agent is connected to Gmail and Google Calendar and handles the day-to-day: email triage, scheduling, recipe suggestions, and medical questions. Think of each container as a locked office. One agent can't peek into another's files. My personal agent has access to my inbox; my business agent doesn't, and couldn't even if it tried. This is a fundamental difference from OpenClaw, where everything runs in a single process and a vulnerability in one area could expose credentials from another.

PostgreSQL runs locally on the Mac Mini and stores everything stateful: conversation history, agent configuration, and per-agent state. Each agent gets its own scoped storage within the database. There's no shared mutable state between them. Running the database locally means no external dependency, no network latency, and no credentials leaving the machine.

Making the Mac Mini invisible to the internet

Here's the core idea: the Mac Mini simply does not exist on the public internet. There are no open ports, no web addresses pointing to it, no way for a scanner or attacker to even find it. The only path in is through Tailscale's encrypted private network, which requires identity-based authentication using cryptographic proof of who you are.

This approach is fundamentally different from OpenClaw, where security depends on the user doing extra work: setting up firewalls, configuring reverse proxies, rotating tokens. With the Blink + Tailscale approach, the secure setup comes first. You don't harden the system after the fact. You start from a position where there's nothing exposed to harden. And because Blink is open source, you can audit exactly how your data is handled. There's no black box between your credentials and the agent runtime.

Here's how the two approaches compare across key security concerns:

| Concern | OpenClaw (default setup) | Blink + Tailscale |

|---|---|---|

| Main service | Publicly accessible | Local only, invisible from the internet |

| Management UI | Separate concern requiring HTTPS setup | Built into Blink Server, one less thing to secure |

| Remote access | Standard SSH (publicly accessible) | Tailscale SSH only (private network) |

| Authentication | Password or token (still maturing) | Cryptographic identity via Tailscale |

| Network discovery | Broadcasts hostname and services | No broadcasts, completely silent |

| Credential storage | All in one shared process | Isolated per-agent in separate containers |

| Multi-agent safety | Shared state where one breach affects all tools | Container isolation with agents walled off from each other |

| Security setup effort | Significant (firewalls, proxies, token rotation) | Minimal (Tailscale install, ~10 minutes) |

To be fair, the OpenClaw community has done impressive work building security guides, and the project's Tailscale integration is a genuine improvement. But the underlying challenge remains: retrofitting security onto a system that wasn't designed for it is always harder and riskier than building security in from day one.

Why I split my agent in two

OpenClaw gives you one agent that does everything. That sounds convenient until you think about what it means: the same process that handles your strategic thinking also has access to your personal inbox. The same context window that holds your business research also holds your medical questions and recipe history.

I initially tried running a single agent that handled everything: business strategy, email, calendar, recipes, health questions. The context window got cluttered, the system prompt got unwieldy, and the responses got worse. When I asked for a competitive analysis of a customer's tech stack, the agent would sometimes drift into suggesting dinner recipes because it couldn't keep the contexts separate.

Blink's container model lets you run specialized agents that stay in their own lanes. Each agent has its own container, its own conversation history, its own credential store, and its own system prompt. They share nothing. If I decide my business agent needs access to my calendar (to check availability before suggesting meeting times, say), I can grant it read-only access to specific calendars without exposing my entire inbox. The permissions are granular by design.

This separation also improves quality. An agent tuned for one domain performs better in that domain. A system prompt optimized for strategic analysis produces worse recipe suggestions, and vice versa. Specialization makes each agent better at its job.

Connecting the agent to real tools

Blink uses what's called a typed integration registry: a structured way to connect your agent to the tools and services it needs. Each integration (Gmail, Google Calendar, Slack, etc.) is a self-contained module that declares what it needs to run (specific credentials or API keys) and what it can do (a set of actions the AI can use). At startup, the system checks which integrations have their required credentials available, activates those, and makes their capabilities available to the agent. The agent doesn't need to know the details. It simply sees a menu of available actions and picks the right one based on what you ask.

This design has a real security benefit: integrations are isolated from each other. Your Gmail integration can't accidentally (or maliciously) access your Calendar credentials. Each module stays in its own lane, with its own scoped storage and its own set of permissions.

Adding a new integration is straightforward: create the module, register it, and deploy. The agent automatically picks up the new tools without any changes to its core behavior or configuration. This means you can start simple (just email, for example) and layer on capabilities over time as your needs grow, without rearchitecting anything.

Reaching the agent wherever I am

A personal AI agent is only useful if you can reach it wherever you already are. Blink supports multi-channel messaging out of the box (Telegram, SMS, WhatsApp, Discord, and more) with a clean separation between how messages arrive and how the agent thinks.

Each messaging channel has a lightweight adapter: a small piece of code that translates that platform's message format into a standard shape the agent understands. The adapter handles the transport; the agent handles the intelligence. This means all the important logic (conversation history, cost tracking, tool use, and model selection) is shared across every channel. No duplication, no drift between platforms.

Adding support for a new messaging platform means writing about 20-30 lines of adapter code. Everything else comes for free.

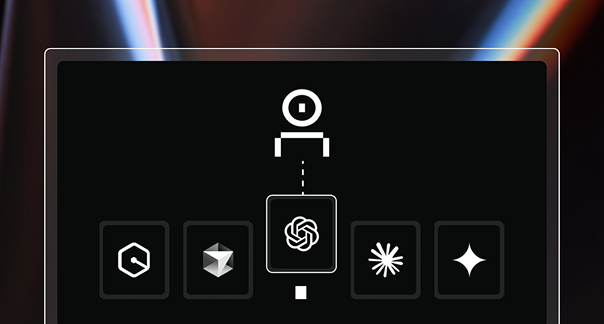

Using the right model for the job

Here's something I learned quickly: not every message needs your most powerful AI model. If I text my agent "Good morning," a lightweight model handles it perfectly. If I say "Search my email for the tax document from my accountant and add the April 15th deadline to my calendar," I need the heavy hitter.

The system automatically routes each message to the right model tier:

Lightweight model (Haiku): Handles simple messages like greetings, acknowledgments, and quick replies. Costs roughly a quarter of the premium model.

Premium model (Sonnet): Handles complex requests that involve using tools, multi-step reasoning, or detailed analysis.

In practice, about 40% of my messages go to the lightweight model, which significantly reduces running costs without any loss of quality for the messages that need full capability. Each response shows which model was used, so I can see exactly where my money goes.

OpenClaw uses a single model for everything, so you pay premium prices even for "thanks" and "got it."

Why iteration speed matters

The first version of any AI agent does the obvious thing. The twentieth version is the one that actually feels useful: handling edge cases gracefully, recovering from errors, maintaining context across long conversations, and responding in a way that feels natural rather than robotic.

This is where Mux comes in. It lets me work on three or four things in parallel: refactoring one piece of the system in one window, prototyping a new integration in another, and stress-testing in a third. Each has its own workspace and its own version of the code, so experiments don't interfere with each other.

Combined with Blink's hot-reload feature (change a file, save it, and the running agent picks up the changes instantly with no restart needed), the feedback loop is remarkably tight. Most of the tuning happens in the system prompt (the set of instructions that tells the AI how to behave), and testing a change is as simple as saving the file and sending a message.

What it actually costs to run

Because the entire stack is open source and runs on a Mac Mini you already own, the ongoing costs are minimal:

| Item | Monthly cost |

|---|---|

| Mac Mini M4 (purchase price spread over 3 years) | ~$19 |

| Electricity (10W around the clock) | ~$1.50 |

| Tailscale (free tier supports up to 100 devices) | $0 |

| AI model usage (varies by volume) | ~$5-15 per agent |

| Database (runs locally on the Mac Mini) | $0 |

A comparable cloud-hosted OpenClaw setup runs $5-15 per month for the server alone, plus the same AI model costs, plus the time you spend on security hardening. With an open-source stack on your own hardware, the only variable cost is the AI models themselves. The Mac Mini pays for itself within a year.

What I learned building this

Set up security first, not last. The temptation is to build everything on your local machine and "add security later." Don't. Install Tailscale before you write a single line of agent code. Develop against the private network addresses from the start, and your development environment becomes identical to your production environment. There's no separate "hardening step" because the secure setup is the only setup.

Start with the right architecture. I initially tried a polling approach (the agent checking for new messages on a timer) before landing on the webhook pattern (messages arrive and trigger the agent immediately). The latter is simpler, faster, and maps cleanly to Blink's container model. Every messaging adapter should be a thin, stateless translator. The agent handles the thinking.

Use built-in storage instead of adding dependencies. I initially reached for Redis (a popular external database) before realizing that Blink already provides per-agent persistent storage. One fewer external service means one fewer thing to secure and maintain.

Specialize your agents early. I started with one agent that handled everything: business strategy, email, calendar, recipes, health questions. The context window got cluttered, the system prompt got unwieldy, and the responses got worse. Splitting into a business agent and a personal agent improved quality immediately. Each agent is simpler, more focused, and easier to tune.

What this means for personal AI agents

OpenClaw proved that the demand for personal AI agents is real. People want an always-on assistant connected to their actual tools (email, calendar, messaging) running on hardware they control. That instinct is sound. And the open-source ecosystem has matured to the point where you can build something production-grade without paying for a single platform license.

But the execution needs to match the sensitivity of the data. A personal AI agent that reads your email, manages your calendar, and sends messages on your behalf is one of the most sensitive pieces of software you can run. Security has to be foundational. Isolation between agents, encrypted credential storage, private networking, and strict access controls are the bare minimum for software that handles your personal data.

Blink provides the agent runtime, the management UI, and the isolation model. All open source, so you can inspect every line of code that touches your data. Tailscale provides the network security. The Mac Mini provides quiet, efficient, always-on compute. Together, they deliver what OpenClaw promises (a personal AI agent on your own hardware) with a security model designed in from the ground up, and no recurring platform fees.

The entire system was built by one person in about two weeks. Good open-source infrastructure does the heavy lifting. Blink handles deployment, state management, and the user interface. Tailscale handles networking and authentication. Mux accelerates the development process. The engineering time goes where it should: making the agents genuinely useful.

That's what good infrastructure enables. You spend your time on the agents instead of on the plumbing.

Getting started

Blink is open source and available in Early Access. Everything described in this article is free to build yourself:

Blink SDK + Server: github.com/coder/blink

Mux: mux.coder.com

Tailscale: tailscale.com (free for personal use)

The quickstart: install Blink, run blink dev, write your first agent, and deploy. Add Tailscale to your Mac Mini and your development machine. You'll have a secure, always-on AI agent in an afternoon, built entirely on open-source tools you own and control.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Want to stay up to date on all things Coder? Subscribe to our monthly newsletter and be the first to know when we release new things!